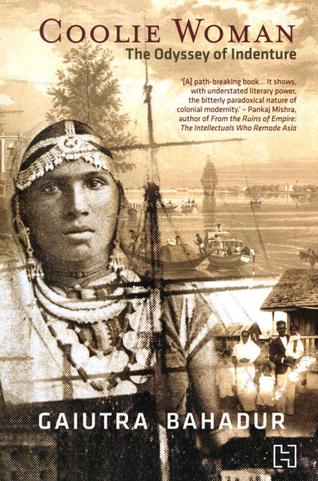

This new contribution to diaspora studies maps a woman’s tumultuous passage from India to West Indies

Usha V.T

Gaiutra Bahadur’s Coolie Woman is an attempt to recreate the journey of an indentured woman labourer — a woman from India —who travelled to the West Indies and eventually to the United States. Diaspora studies have often pointed out that a wide array of social and economic deprivations drove villagers from their homes to travel to faraway lands. And as this author reiterates, the practice of imperial capitalism destroyed traditional livelihoods, while at the same time colonialism created new routes for moving across the subcontinent, in several guises.

The author justifies the use of the term coolie , despite its derogatory connotations, at the very outset. In fact, she devotes a whole chapter to a discussion of the term and its use in the current context. “As it turns out, mystery darkened the lives of many women who left India as coolies. The hind of scandal was communal. Some historians have called indenture “ a new form of slavery,”

In many ways it was: once in the sugar colonies, coolies suffered under a repressive legal system that regularly convicted more than a fifth of them as criminals, subject to prison for mere labor violations, which were often the unjust allegations of exploitative overseers.”

What makes the work interesting is the autobiographical nature of the narrative. The protagonist is the author’s great grandmother Sujaria, whose life and adventures are the occasion to map the tumultuous journey of the woman from her home in India to the West Indies. With the help of historical records, legal documents and tales of indenture, Gaiutra Bahadur attempts to recreate her grandmother’s historic journey. She says: “What I found was a revelation. I once thought that my great grandmother must have been an exception .” And a little later we read: “In which category of recruit did my great grandmother fall? Who was she? Displaced peasant, run away wife, kidnap victim, Vaishnavite pilgrim or widow? Was she prostitute…”

The sexuality of the women and her exploitation in terms of her body both during the journey to the new land as well as in her survival in the land of her slavery through sexual negotiation takes prime place in some of the seminal chapters of the book. They were exploited physically and their reputations were then “dismembered”. This was done systematically both by the men who exploited them as well as by the men who had no sexual stake in the women. Though it was seen that gender imbalance caused sexual chaos in the colonies among the indentured labourers and their functionaries, the women were made to suffer not merely physical agony but mental torture through character assassination. Some of the comments and statements that Gaiutra cites are from public figures held usually in high regard: Even men without a sexual stake in the women cut them to pieces. The Reverend C.F Andrews, indenture’s greatest critic, rued the women he met in Fiji. “The Hindu woman in this country” he reported, “is like a rudderless vessel with its masts broken being whirled down the rapids of a great river without any controlling hand. She passes from one man to another and has lost even the sense of shame in doing so ”.

Of course none of the opinionated colonisers bother to talk to the women or ask for their version of the reality they face on an everyday basis for survival. Yet they make their judgements on the character of the women vocal and the woman as always is silenced and humbled for circumstances beyond her control.

In 1906, the author’s great grandmother and her new born arrived at Rose Hall Plantation, on Canje Creek. She did no field work there as the narrator informs us… “Dey send her, and she cyaan make it in the field, because her feet was soft …” Instead Sujaria was assigned to be a child minder. This was the job that Jamni, the woman at the edges of the Nonpareil uprising, either as kept woman or rape victim, reportedly had. And this was the job that my great grandmother was given. Perhaps this was because she had a baby to support alone and her caste background had made her useless in the fields. Or perhaps, she possessed a pretty woman’s advantage. (p 148)

Gaiutra explains how caste class and gender are factors that develop new meaning as the woman moves from her own land through along, perilous journey into a new world where her survival depends on her capacity to negotiate with the multiple forces that are decisive to her existence. Her sex, though her weakness, now becomes a major factor that she can utilise for negotiating her survival. In a way of life, that is exploitative, survival become the centre of the labourer’s existence and the author explains how it is achieved in individual cases.

The narrative is supported with documents such as legal references, captains’ or doctor’s logbooks from the ships, police records, administrative reports, photographs etc.

These neglected narratives are footnotes to colonial history and women’s history in particular. It becomes her middle passage:

middle-passaged

passing

beneath the coloring of

desire

in the enemy’s eye

a scatter of worlds and bro

ken wishes

in shiva’s unending dance

(Arnold Itwaru, “We Have

Survived”)

With an astute eye for detail Gaiutra Bahadur, trained as a journalist, unearths sumptuous information buried in documents and records hitherto less-explored areas pertaining to women in indentured labour amounting to sexual slavery, and the odyssey of indenture is presented in a nonchalant manner. However having said that, the documentary nature of the work makes it a little tedious and uninteresting at times over several pages.

The author’s self-conscious struggle to motivate the reader to share individual experiences — albeit factual, in places slipping into a fictional style — is sometimes a bit laborious and too obvious. Gaiutra Bahadur’s Coolie Woman traces the story of how one woman’s experience represents an entire spectrum of woman’s experience: the book is a veritable source book for further research in diaspora studies.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> Book Review / by Usha V.T / September 16th, 2014