At a time when politics of hate threatens to tear apart the inclusive social fabric of the state, such stories demand a telling.

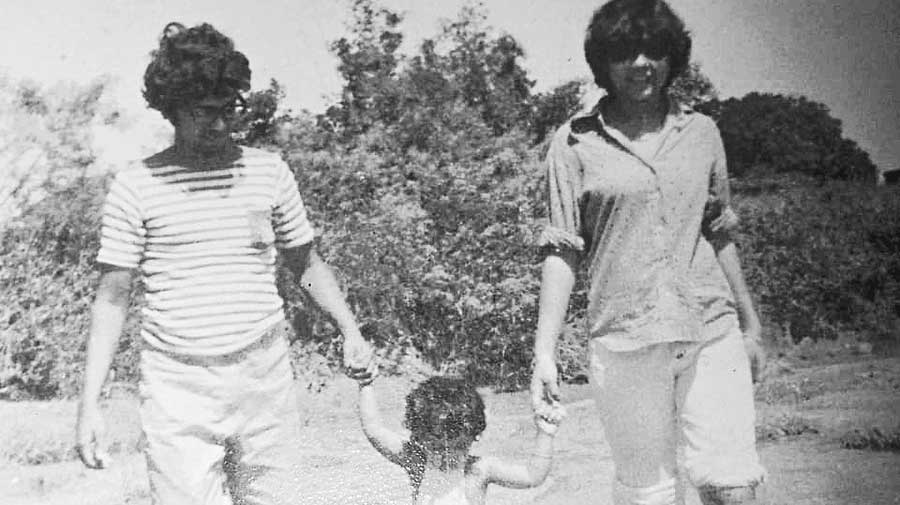

Gautam Sengupta is 69. Yasmeen Sengupta is 65. He is a Hindu. She is a Muslim. Married for 46 years, the two have lived through many ups and downs. Their families have always stood by them.

Till their health permitted, Yasmeen used to paint alpona during Saraswati Puja at her in-laws’ ancestral home in Park Circus every year and Sengupta broke bread with her during Ramazan.

There are many like the Senguptas of Park Circus around Bengal. But such stories demand a telling because of the politics of polarisation that threatens to tear apart the inclusive social fabric of Bengal.

Jesuit culture, Tagore

Yasmeen’s family shifted from Ballygunge Place to Circus Row when she was nine years old. Sengupta’s family home stood a stone’s throw from the Park Circus Seven-Point intersection. The two got introduced through a set of common friends and got married in 1975.

Sengupta, who did his school and college from St. Xavier’s, holds Jesuit principles close to his heart till this day.

Yasmeen did her school from South Point and graduated from Loreto College. Yasmeen’s grandfather, Rafiuddin Ahmed, is the founder of the R. Ahmed Dental College, the oldest such institute in Southeast Asia.

But her inspiration is her grandmother Ayesha Ahmed, an alumnus of Brahmo Balika Shikshalaya. Later, Ayesha was part of a group of women who started a school for girls from marginalised families in Beleghata, which is now called the A.I.W.C Buniadi Bidyapith Girls School.

She made Rabindranath Tagore a part of the lives of the Ahmed family.

Yasmeen and Sengupta got married in Brahmo tradition. “There was hardly any ritual. I remember my friends singing Tagore songs,” said Yasmeen.

“When we were growing up, inclusiveness was not just a textbook word. It was a part of our everyday lives. Every home had pictures of Tagore, Gandhi, Vivekananda and Netaji,” she said.

Sengupta remembered growing up in a neighbourhood where the president of the local Durga Puja committee was a Muslim and the treasurer a Christian.

Sengupta, who runs a manpower consultancy firm, has turned a part of his ancestral home into a guesthouse. The couple also own a flat in the Hastings area and keep shuffling between Hastings and Park Circus.

‘Heroic’ acceptance

One of Sengupta’s grand-uncles (father’s uncle), a doctor, was killed during the 1947 riots. “A man disguised as a woman in a burqa entered his chamber as a patient and shot him point blank,” said Sengupta.

But the past never came in the way of the Sengupta family embracing their daughter-in-law. “My family members always considered the incident an act of terror, an aberration in a moment of madness,” he told this newspaper.

“Their acceptance of me has been absolutely heroic. We (her parents and in-laws) speak the same language, eat similar food. It is not like I was wedded into an alien culture. But the way they rose above petty human instincts was heroic,” said Yasmeen.

The couple have a daughter and a son. Their daughter, Rohini, is married to a Muslim man. The two are settled in Sydney. The bride and the groom’s family had known each other for three generations and the couple knew each other from childhood.

“The marriage happened in 2001. It was such a happy occasion,” Sengupta said. His no-fuss demeanour drove a point home. That some of the stereotypes associated with interfaith marriages are based more on myths than reality. That an interfaith marriage can still be a normal and spontaneous affair.

Yasmeen, a social worker, keeps reading newspaper reports and seeing television programmes around “love jihad” — a Right-wing narrative of Muslim men marrying Hindu girls with the alleged intention of converting and radicalising them.

At least two BJP-ruled states have introduced legislation criminalising interfaith marriages if conducted for the ostensible purpose of religious conversion.

“Where is the individual freedom, guaranteed by the Constitution? This is a blatant violation of constitutional values. Not only is this bad in principle, it is also bad in law,” said Yasmeen.

Fear of tomorrow

“I am terrified of the future,” Yasmeen told this reporter bluntly. She is worried because she has heard plenty of stories of Partition from her elders and she dreads a rerun.

“Politics now thrives on polarisation, more so in the run-up to the elections. Bengal and Punjab are two states scarred by Partition. Both places have seen how polarisation brings out the basest instincts in people. I have grown up around people who saw best friends baying for each other’s blood during Partition,” she said.

Sengupta has spotted a change in the social fabric of Bengal. “A section of people now asserts their religious identity more strongly than before. Wearing your religion on your sleeve is the norm,” he said.

The next second, he gave a caveat. “I have never been too religious. Perhaps that’s why I notice these things more than others.”

Sengupta remembers some “flare-ups” in his neighbourhood in the aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992 and surrounding author Taslima Nasreen, who was eventually “expelled” from Bengal in 2007.

Sengupta stood up to a mob with sticks and flaming torches intent on setting a series of taxis on fire. “I managed to prevail on them. They were fuming but went back. Most of them were local boys,” he recounted.

Both the husband and wife said the ongoing polls are more than a battle for political power. “We don’t know if it is possible to get back the Bengal where we got married. But we still have a place where all kinds of people live together. We must try to preserve what we have,” Sengupta said.

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph Online / Home> West Bengal / by Debraj Mitra, Calcutta / April 19th, 2021