The Canadian-turned-Calcuttan did not share the disdain arty Indian filmmakers had for commercial cinema.

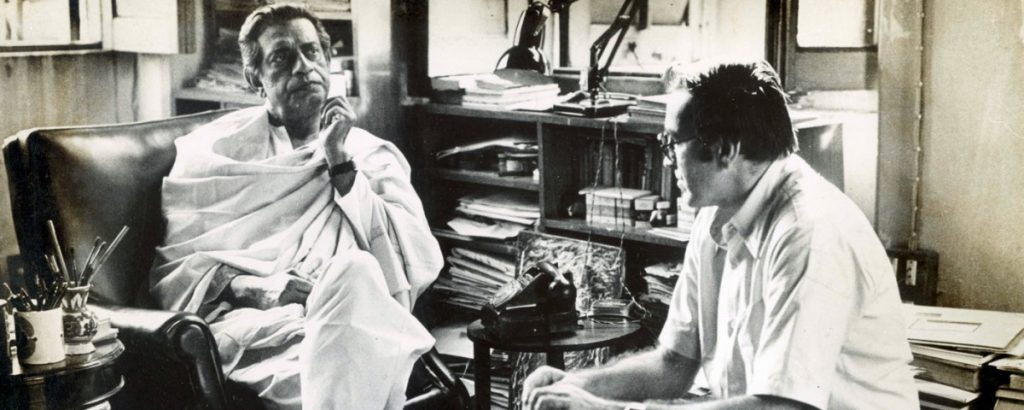

The exchange between the little prince and the fox from the classic 20th century post-war French fable, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince, holds the key to how two men – Satyajit Ray and Fr Gaston Roberge – met every Sunday at 9 am at the residence of Ray on the Bishops Lefroy Road in Calcutta. Like the fox and the prince, they kept their ritual and explored the world of ideas. Alas, now with the passing of Fr Gaston Roberge, we will never know who was the prince or the fox between the two. This rite of friendship lasted for 22 years, ever since their first meeting in 1969. They institutionalised their friendship in the form of Chitrabani, the first development communication institution in the eastern part of India, and thus the lore continues.

Unlike their rendezvous, I encountered Fr Gaston Roberge on three occasions, serendipitously – in Pune, Ahmedabad and Goa – in the early 1990s. The third time, at an International Canadian Studies conference, I decided to record the moment in the form of an interview which was then published in the Sunday Magazine of the Indian Express on November 13, 1994. Each time it was his Canadian cadence of directness, and unassuming presence, coupled with the mischievous smile and the phenomenal capacity to talk cinema that stood out.

Let’s take the case of the blockbuster hit Sholay. This year marks the 45th anniversary of its theatrical release in 1975, and I do not recollect anyone who has brought together the arrival of the train at the Ramgarh and the Lumière brothers’ 50-second shot of L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat in Paris (1896) together in a sentence: It is in such moment of equivalence that one is deschooled and taken on a parallel journey of Indian cinema.

For Fr Roberge, “a proud Calcuttan”, embedded in culture and ethos of the host society – becoming native was a natural process. “I am at a loss when I am asked, ‘Where are you from?’,” he confesses. “I have been called ‘Fadar Gautam Roberjee’,” he said, recounting an incident of his earlier days after his arrival in Kolkata while learning the Bengali language and doing missionary work in the schools. When asked how he felt about that name, an accident of accents, he smiled. “I like it! I still use ‘Fadar’, he said to me. Fadar speaks Bengali with a French accent among other languages like Italian. Through interacting with Bengali people, I have come to know myself further,” he had said.

Writing about his journey to India, he said it was an “urge” to come over to India, to dialogue with her people, and learn from them whatever he might discover that he did not know, especially about God. “In return, of course, I was keen to share whatever my own tradition had given me. But my journey was one of discovery, not of colonization, religious or political. I had joined the Society of Jesus at the age of 21 years. I already had five years of religious life when I volunteered to come to India, and my superiors decided I would join the Jesuits of Kolkata.”

I recollect him telling me how the city was encoded in him in form of a tri-murti, an image with three faces: “the face of cineaste Satyajit Ray, Mother Teresa, the face of the rickshaw-puller in Dominique Lapierre’s The City of Joy—each representing the creativity of the intelligentsia, unconditional charity and the heroism of an ordinary citizen.” He had a very close relationship with both Mother Teresa and Dominique Lapierre.

In drawing attention to the imperative to think about cinema, he implores, “thinking allows the mind to progress in its search for plentitude and unity. When one is dissatisfied with a particular social order, one is tempted to reject the type of thinking that is associated with that order. This is indeed a mistake. For, if one cannot transcend the limitations of a social order with the help of the ideology of that order, one is not likely to be able to transcend the limitations of the alternative social order either, with whatever ideology.”

Writing was his mode of thinking – at the last count he had authored 31 books – especially after he discovered his inability to do much on the field during the violent times of the 70s in Calcutta during which many conspiracy theories flourished, making him, his work and the institution of Chitrabani the suspects of an international conspiracy, ranging from cold war rhetoric to missionary conversions.

The confluence of Derrida and his missionary invocation produces statements like:

“A text always already defies the authority of its author. What is true of films is generally true of all texts. The author of a text, filmic, literary or dramatic, is not the author—God.” (original stress)

In conversations, his pauses and the idea of silence were eloquent and an exercise in listening, an endangered practice as Nuruddin Farah would say. His witty deployment – “I am a priest” – as a strategic reminder of drawing the line in refraining to speculate in a discussion despite being tempted intellectually.

Woven into his discourse were emotion and theology and implicit in his teleological imbuement of Cinema was the providentialism. Once I asked him about Kalaignar Karunanidhi writing out god from the Tamil cinema. He paused and alluding to the 17th century tension between Blaise Pascal and Rene Descartes, who tried to dispense with God in philosophy, and quoting Pascal said, “the heart knows of reasons that reason cannot grasp”. Much like a Bernard Crick, he elaborated the treatise in defence of Indian cinema. “[P]opular films are collective dreams and song and dance is an integral part of it. Song and dance are sight and sound,” he wrote, invoking Bharat Muni’s Natyashastra. He was the Master Preacher of Film Theory, as the 2017 39-minute long documentary by K.S. Das encapsulates the remarkable Father Gaston Roberge.

Among the critical three decades of the 70s-90s, it was in the 80s that his work bore much meaning as filmwallahs, writers, academics, critics and even politicians were flailing in an effort to keep their feet on shifting ground, as everything was up for question.

At the beginning of the 80s, the film society movement, having spread across the nation fostering an orientation of an alternative film culture with an international outlook, found itself in a crisis as it embattled the state bureaucracy’s wrongful interpretation of its activities – sites of commercial entertainment. At the same time, as questions about Indian cinema became part of a milieu for the 800-odd graduates who had come out of the Pune Film Institute, brandishing “a consciousness of the social responsibility of the artist”, as Jagat Murari wrote about as the mandate of the institute. Fr Roberge countered the dismissive and patronising gaze of the film society-wallahs, as he sought answers in a fuller engagement with the popular Indian cinema. In response, Fr Gaston offered Another Cinema for Another Society, a militant manifesto of sorts: “A new cinema can only be born along with a nascent society and a new cinema can contribute to the growth of that society. ”

Similarly, the two key reports – the Patil Report of the Film Inquiry Committee (1951) and Karath Report of the Working Group of Film Policy (1980) – are like bookends to the bureaucratic rationalisation of the political economy of the Indian film industry. Often the disdain was visible, as the Karath report framed the film industry, “vulgar, trivial, reactionary, tasteless and exploitative”.

With his trademark clear-headedness, Fr. Roberge defined his position:

“Every effort should be made to salvage from total oblivion the report of the Working Group on National Film Policy (1980) for a new Indian Cinema. The report has ideological limitations but argues well for ‘another’ Indian cinema. This cinema would take on the social tasks which critics of the so-called commercial cinema want the latter to perform. In our socio-economic system, commercial cinema functions best when it is is spared the irritant of false expectations, and when the social value of the commodity it produces—entertainment—is recognised.”

He was a faithful witness to these turbulent times as Indian cinema was in the throes of its identity crisis – “good Indian cinema” vs “radical cinema” – as the questions of a ‘third cinema’ began floating around.

There were many endeavours in that decade in search of the quintessential Indian idiom.

Earlier, Satyajit Ray laid out the schema in Our films, Their films. As Chidananda Das Gupta was Talking About Films, we read that Kishore Valicha had pronounced Amitabh Bachchan as the urban machine. In the context of the Sikh pogrom, Nirmal Verma proclaimed at the Gandhi Peace Foundation the need to address “religion, the most prestigious thing in the life of every Indian. Why should we in the name of this faithless secularism try to deny the deepest, the noblest quality of Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims, every religion?”; K.S.Singh and Bapu Jayasinhji Jhala were trying to institutionalise visual anthropology in India; G.N. Devy was calling out the amnesia in literary criticism; Arundhati Roy scripted and acted in, In Which Annie Gives it Those Ones; and, Pankaj Mishra was still on his way to Ludhiana for his butter chicken!

Despite cinema as his apostolic calling, he resonated with Arturo Escobar in the critique of development: “Sustainable development is an oxymoron and is not some project but a quality of human mind”. In the same vein, he added, “Spirituality is not a part of any religion but a quality of humans.”

With his friend Apu and uncle Bharat Muni, he made his way through the cinematic maze, addressing the poverty of Indian cinema, enriching the Indian people through a mass literacy in the means and technologies of communication as tools of conviviality.

Displaying admirable epistemic fluency, patience, discernment and prescience, the way Verrier Elwin responded to the tribal question, Fr Roberge did on the question of communication, and for him, the modality of cinema became a point of entry into that communication—human communication. All his life, Fr Roberge argued and endeavoured to define the social contract of image making in India, which unfortunately is under duress once again.

Narendra Pachkhédé is a critic and writer who splits his time between Toronto, London and Geneva.

source: http://www.thewire.in / The Wire / Home> Film / by Narendra Pachkhede / September 01st, 2020