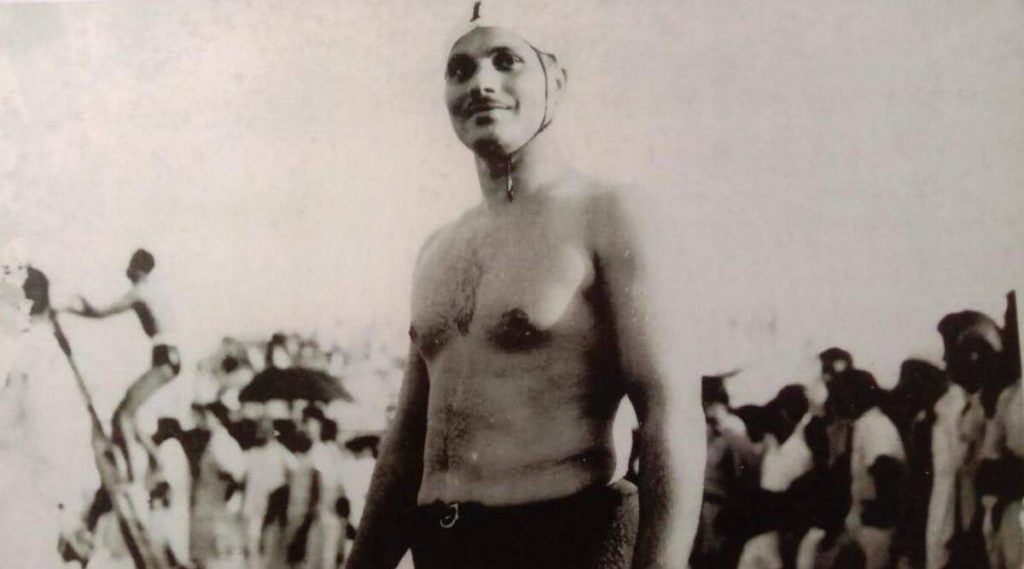

Swimmer Sachin Nag, who won the country its first gold medal at the inaugural 1951 Asian Games in New Delhi, gets Dhyan Chand Award

Ashoke Nag talks about having sleepless nights before the national sports awards were announced earlier this month. The son of late swimmer Sachin Nag, winner of the first gold medal for the country at the 1951 Asian Games in New Delhi, had experienced rejection in the past when he tried to secure his father’s legacy.

This was the fifth time Ashoke had applied to the sports ministry to bestow an award posthumously to one of Independent India’s first sporting superstars.

His father passed away in 1987 ‘with a broken soul’, Ashoke says.

Armed with 47 supporting documents, including black-and-white paper cuttings, certificates and a recommendation from paralympic swimmer Prasanth Karmarkar, Ashoke, a former sergeant in the Indian Air Force, applied again this year. The willpower to fight for the recognition his father deserved grew stronger every year that Sachin Nag’s name was not included in the list of awardees. 2009, 2012, 2018 and 2019 had brought only heartbreak.

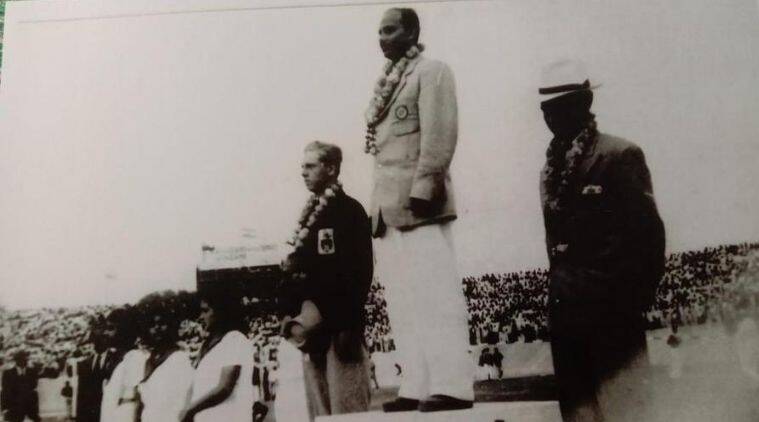

“This year, I had reason to be hopeful because it is his birth centenary. And remember, he won three medals at the 1951 Asian Games. The gold in the 100m freestyle and bronze medals in the 400m freestyle relay and 300m medley relay. This was just four years after independence. India was a young country, those medals mattered a lot to the nation. I felt frustrated in the past when my father’s name was not included. My father passed away with a broken soul,” Ashoke, who has also penned his father’s biography in Bengali, says.

On Saturday, Ashoke will attend the online awards ceremony at the Sports Authority of India centre in Kolkata, where the president will virtually bestow the Dhyan Chand Award to his late father. “I attended the rehearsal on Thursday. I met archer Atanu Das and sprinter Dutee Chand. Felt good to be in the company of young achievers. I am looking forward to Saturday. After applying for the award, I would wake up at night and wonder if this would be the year,” Ashoke says.

As time went by, Ashoke knew he was in for a long battle.

The family had generously handed over Nag’s medals and blazers to the museum at the National Institute of Sports in Patiala in 1992, five years after the swimmer passed away. Nag was also a two-time Olympian and also part of the Indian water polo team. He coached for three decades as well. Ashoke felt his father got nothing in return after the initial fanfare died down.

Former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Lady Edwina Mountbatten watched the event at the pool in 1951, Ashoke says. “Nehru ji was the first one to congratulate my father poolside when he won the gold in the 100m freestyle. I have pictures of Nehru ji and my father together. My father would say PM Nehru gave me respect but at times he felt that over the years people had forgotten him,” Ashoke, the third of six children, says.

Nag, according to his son, was a proud man. He never asked for favours. Ashoke remembers how his father shot down the idea of approaching a top Swimming Federation of India official to recommend his name for the awards after they were instituted in 1961. “My father said, ‘I used to beat him in the 100m freestyle in the pool. I can’t go and ask him for a favour just because he has become a powerful official.’ He was a proud man,” Ashoke recalls.

Hurtful barbs

Some of the barbs Ashoke faced over the years still sting. Once after the awards were announced, he asked a footballer on the committee what went against his father. “The footballer asked me, ‘how many times did your father represent India? The footballer himself had won the Dhyan Chand award earlier. Yet he insulted my father by asking that question. It hurt me back then,” Ashoke says.

Nag had to deal with official apathy in the run-up to the 1951 Asian Games. The games were scheduled for early March, but Nag had arrived in Delhi in December, hoping to train in the capital. “An official of the organising committee asked my father why he had come so early and told him to go back to Calcutta. He was told there were no swimming pools in Delhi that he could use. But my father decided to find a way to train in Delhi. He located Sisil Hotel in old Delhi, which had a 20m by 10m pool, and requested an Italian lady who was the manager to allow him to use it for training. She agreed for a fee of about Rs 5. That too was waived off later.”

When he won the gold at the Asian Games a few months later, one of his first stops was the hotel. “He went to Sisil hotel to thank everyone for the support. He always remembered those who supported him.”

Caught in riots

If not for Nag’s steely determination, his swimming career would not have reached the heights it did in the late 1940s and early 50s. Nag suffered during the tumultuous days of Partition when he inadvertently got caught in the Calcutta riots. “He was returning from training at the Ganges when a bullet hit him on the right leg. He was badly injured and was admitted in a hospital for five months. When he was being discharged, the doctor told him that it would take him two years to get back to swimming,” Ashoke says.

But in a year’s time, Nag was at the 1948 London Olympics. He participated in the 100m freestyle and was a member of the Indian water polo team that beat Chile 7-4. All four goals were scored by Nag, Ashoke says.

To speed up his recovery, Nag returned to Banaras, where the family was based. He returned to the pilgrim town to rejoin the Saraswati Swimming Club, which he had founded. The masseurs in Banaras were excellent.

Another incident connected to the freedom struggle, where a young Nag was chased by police who were trying to break up a protest, resulted in his swimming talent being discovered early.

Ashoke narrates the sequence of events. “My father jumped into the Ganges to give the police the slip. He first hid underwater between two boats. But how long can someone stay underwater? There was a 10km swimming competition starting in the river and my father joined them. He finished third,” Ashoke says.

Back then, reputed swimmers from Calcutta clubs would enter long-distance competitions in Banaras. One of them, Jamini Das, who would captain the national waterpolo team at the 1948 Olympics, believed Nag had great potential and asked him to shift to Calcutta where he joined the Hatkhola Club.

One of Ashoke’s cherished memories from his childhood was his father pushing him and his brothers into the Ganges to swim. “We never became top-class swimmers like our father. But being successful in getting my father the prestigious award gives me immense satisfaction.”

source: http://www.indianexpress.com / The Indian Express / Home> Sports / by Nihal Koshie / August 29th, 2020