According to historian P Thankappan Nair who has extensively documented Calcutta’s history, the name ‘Topsia’ may have been derived from the fish species Polynemus paradiseus , also known as the ‘topshe’ fish found in the waters of West Bengal, Bangladesh and elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

The tanneries that once choked the bylanes of Topsia have long gone, shifted to the outskirts of the city. But a decade later this eastern neighbourhood of Kolkata has found it difficult to shed the association with the industry even though the pungent smells of the neighbourhood — a combination of tannery fumes and effluents, open ditches and the garbage landfill sites at nearby Dhapa — have long dissipated.

Several neighbourhoods have come up in the East Kolkata wetlands despite its ecological importance and for decades the area was home to the city’s tanneries that caused severe environmental degradation. In 1996, the Calcutta High Court ordered the tanneries to be relocated outside the city limits, a process that took at least another decade to fully materialise. Following the court order, the tanneries slowly left the neighbourhoods of Tangra, Topsia and Tiljala, only to be replaced by construction companies that swooped in and began filling up the wetlands to develop the area for residential and commercial purposes, despite it having been declared a Ramsar site in 2002.

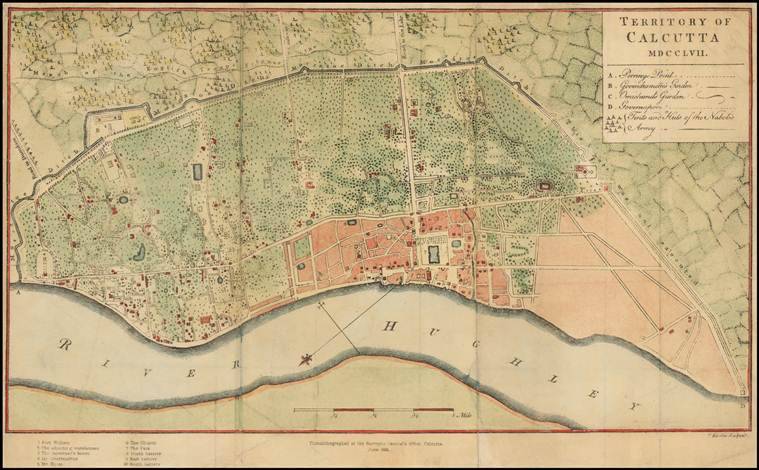

Topsia became a part of the burgeoning metropolis of Calcutta in 1717 when the British East India Company rented 38 villages surrounding the city from Mughal Emperor Farrukhsiyar. The Company went on to purchase 55 villages, including the 38 that it had previously rented, from Nawab Mir Jafar in 1758 and incorporated them all as the outer fringes of the developing city.

The villages collectively came to be known as Dihi Panchannagram, the literal meaning of which is “55 villages”, and lay outside the Maratha Ditch, an approximately 5 kilometer ditch that was excavated in 1742 to form a perimeter around Calcutta to protect the British from the Maratha invasion that never came. The Maratha Ditch, built for the protection of the British, was entirely funded by taxes paid by Indians.

The villages that formed Dihi Panchannagram fell outside the Maratha Ditch despite being a part of the city of Calcutta. Their incorporation into the city limits occurred more completely when the Maratha Ditch, having been a useless enterprise, was partially filled in 1799 and then entirely in 1893. Harry Evan Auguste Cotton, an English barrister and historian who lived in the city during that time and wrote about Calcutta in his book ‘Calcutta, Old and New’, refers to the 55 villages as the “suburbs” of Calcutta that had been separated from “the 24 Perganas” and added to the city of Calcutta by Mir Jafar in 1757. “For revenue purposes they formed part of Calcutta, but their legal existence was separate and distinct,” wrote Cotton. Topsia, as part of the Dihi Panchannagram, finds mention in Wood’s map of Calcutta of 1784 and A. Upjohn’s map of Calcutta of 1794. Today, this area is still known as Panchannagram, the term ‘Dihi’ having gotten lost over the centuries as street names got diluted and changed in the city.

Due to the presence of the wetlands near Topsia, historical records show that fishing was one of the main sources of livelihood for many in the villages and it may also be how the villages collectively got this name. According to historian P Thankappan Nair who has extensively documented Calcutta’s history, the name ‘Topsia’ may have been derived from the fish species Polynemus paradiseus, also known as the ‘topshe’ fish found in the waters of West Bengal, Bangladesh and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, and the name has continued to be used till date. Prior to the reclamation of the East Kolkata wetlands, the fish was found in relative abundance in the waters and was a staple for the people living in the villages in the area.

Over the years, as Kolkata expanded and migrants from nearby towns and states relocated to the city for work, tanneries developed near the wetlands because the neighbourhood was still considered to be the outer fringes of the city. Many of these migrants found low-paying, physically challenging jobs in the tanneries, living and working in cramped quarters, with little hygiene and access to resources and even less impetus from the government that did little to better their working and living conditions. Although reports of severe pollution and improper disposal of waste as a result of the tanneries had been circulated for years, it took a court order issued by the Calcutta High Court in 2008 to lead to an official crackdown on the tanneries operating in the area, several illegally, and resulted in the relocation of operations outside the city limits. During the last three decades, as the area witnessed rapid development and land reclamation, it slowly became more fully absorbed into the growing metropolis of Kolkata. Today, it also serves to connect central Kolkata to the Salt Lake neighbourhood, Rajarhat and the airport beyond.

Topsia is a juxtaposition of slums, haphazard residential accommodation and luxury hotels that have paved the way for aggressive modern construction on a larger and wider scale in the sensitive wetland area, that shows no signs of stopping despite protests over the years by environmental activists.

These days, the ‘topshe’ fish can be found in Kolkata’s local markets, brought to the city after having been harvested elsewhere. The fish that gave Topsia its name, however, would be hard to find, if not entirely impossible, these days in what remains of the waters of wetlands.

source: http://www.indianexpress.com / The Indian Express / Home> Cities> Kolkata / by Neha Banka / December 03rd, 2019