Kolkata’s decision to rename Park Street after Mother Teresa is a perplexing one, since she had little to do with the thoroughfare and its environs, but the street’s name change is hardly a new occurrence.

In 2004, Mayor Subrata Mukherjee announced that the Kolkata Municipal Corporation would be renaming several streets and roads in the city after prominent Indians and residents of the city, a change that would divest street names of their colonial identities. The renaming of city streets continued for the next decade by subsequent governments but for residents of the city, British colonial street names have been remnants that have been hard to shake off. Despite the name change, one of the city’s main thoroughfares, Park Street, is rarely referred to by its relatively new nomenclature, Mother Teresa Sarani, even on most government documents and during government-organised street programmes. The street’s colonial nomenclature is thus as iconic as the street itself.

Documented records of the street itself can be traced to 1760 when the city was still called Calcutta and was the capital of British India. The city’s decision to rename Park Street after Mother Teresa is a perplexing one, since she had little to do with the thoroughfare and its environs, but the street’s name change is hardly a new occurrence. Since 1760, the street has seen several name changes as Calcutta consistently swelled and developed into a larger metropolis. The first known name of the street can be found in the ‘Bengal & Agra Directory of 1850’ where it went by the name of ‘Ghorustan ka Rastah’ or ‘Badamtallee’ and “open(ed) on Chowringhee opposite the ‘Chowringhee gate’ of the fort, (ran) easterly to circular road.”

In 1760, the East India Company appointed Henry Vansittart as the Governor of the Presidency of Fort William in Calcutta and set him up in a large three-storey colonial mansion at No 5, Middleton Row, a relatively small street that was a bylane off the main thoroughfare that is now Park Street. That three-storey residential structure had a large garden attached to it, as was the common architectural layout during that time and served as the residence of Vansittart during his four-year governorship in Calcutta.

Vansittart’s tenure in Bengal was rife with misconduct and reports of widespread corruption that resulted in him being forced to step down followed by his departure for England in 1764. His residence was emptied and occupied by Elijah Impey, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William, Calcutta in Bengal.

Impey too took advantage of his position as Chief Justice. A friend of the then Governor-General of Bengal Warren Hastings, Impey tried Maharaja Nandakumar, a diwan in Birbhum, on charges of fraud. But Hastings had framed the charges after Nandakumar reported him for wrongful appropriation and embezzlement of public property. Impey himself oversaw the trial and pronounced Nandakumar guilty of the charges. The Maharaja was hanged in Calcutta in 1775.

After the hanging of Nandakumar, Thomas Macaulay accused Impey of judicial misconduct and Hastings of misconduct and corruption and brought on a seven-year-long impeachment hearing against the two. At the end of the impeachment process, both were exonerated by the British House of Commons, mainly owing to domestic political reasons in Britain and not because of findings of any investigation. Both went on to live comfortable lives in Britain.

Historian P. Thankappan Nair traces the origins of the name Park Street to the expansive gardens around Impey’s residence. The area occupied by Impey’s residence and the adjoining gardens were so large that it included the grounds on which Loreto College now stands. Some records say the residence extended all the way from Middleton Row to Russel Street and included the grounds that now belongs to the Royal Calcutta Turf Club, now unused and in dire need of maintenance. Other records claim the gardens had deer running around, because of which the grounds began to be called a deer park, but there don’t seem to be any existing documents that confirm this.

Other names of the street through the city’s history have included Badamtalla, or Almond Street, Vansittart Avenue, Burial Ground Road and Burial Ground Street. Henry Ferdinand Blochmann, a German scholar who was fascinated by the Indian subcontinent and studied and taught Persian during the 1860s in Calcutta, has documented the history of the city and it’s streets during the 18th century in his book ‘Calcutta During Last Century’. Park Street, writes Blochmann, was called Burial Ground Street and “had about ten houses lying along it”.

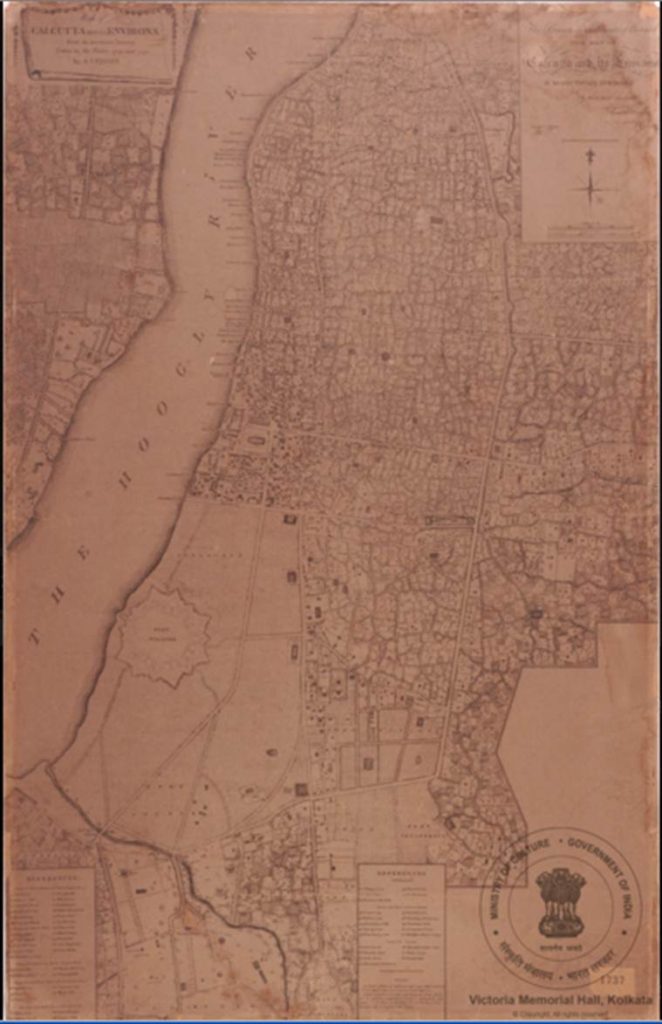

In A. Upjohn’s map of Calcutta, 1794, Park Street is referred to as Burial Ground Road, because it was the path that funeral processions took to reach the South Park Street Burial Ground that opened on August 25, 1767. Due to this, for a long time, the street was not a preferred choice of residence. The Park Street area also had the North Park Street, Mission and Tiretta burial grounds before they were flattened to make way for other establishments. The Apeejay School now stands on the remains of a razed French cemetery and while the Assembly of God Church Tower stands on the site of the North Park Street Cemetery. The only visible remnant of the North Park Street Cemetery is the Robertson Monument, a grave for the Robertson family whose members served in Kolkata Police. According to historians who have traced the structure’s history, it was only this connection of the family with the Kolkata Police that prevented the monument from being served the same fate as the rest of the tombs on the North Park Street Cemetery. Today, the monument stands in one corner of the pavement, outside the Assembly of God Church Tower, coated in grime from passing vehicles and drowning under surrounding billboards and the hanging mass of tangled wires and cables, easy to miss if one isn’t paying attention.

It isn’t clear when the name changed from Burial Ground Road to Park Street, but given its association with Impey’s “deer park”, it can be assumed that the transition occurred sometime around the 1760s during Impey’s tenure in the city. According to city records, Park Street extended from Chowringhee to Lower Circular Road till 1928 when the Calcutta Improvement Trust extended the portion on Lower Circular Road to the city’s railway lines at E.B Railway Bridge Number 4. The extension of Park Street at its southern end was completed in 1934 and found mention in that year’s government gazette.

Despite its earlier association with the four burial grounds in its area, the long stretch of the street rapidly developed over the centuries to accommodate residential mansions and educational and religious institutions like St. Xavier’s College, the Freemason’s Hall, the Asiatic Society of Bengal etc. In recent decades, especially post the Second World War, many of the city’s iconic structures on Park Street have been steadily razed to make space for modern construction and the architecture of the street has changed. Today, the mansions are fewer, as are the neighbourhood’s residents who have seen Park Street rapidly change over the past four decades. Restaurant chains, cafes and sari shops with neon sign-boards have taken over the colonial structures that once housed residential apartments and government offices. The last burial ground of Park Street may soon be the only remaining witness of what the thoroughfare once was and its history.

source: http://www.indianexpress.com / The Indian Express / Home> Cities> Kolkata / by Neha Banka, Kolkata / December 03rd, 2019