The list of alumnae who played a significant, if less acknowledged role, in India’s freedom struggle is a lengthy one, and includes those who took up arms in their war against British rule and oppression.

Bina Das was only 21 when she opened fire on Bengal Governor Stanley Jackson at Calcutta University in 1932. But in Calcutta’s Bethune College, women like her were not rare. In fact, the institution played a pivotal role in shaping women like her, especially those who called undivided Bengal their home, who fought for freedom from British rule.

The list of alumnae who played a significant, if less acknowledged role, in India’s freedom struggle is a lengthy one, and includes names like Kamala Das Gupta, Kalpana Dutta and Pritilata Waddedar who took up arms in their war against British rule and oppression. There are also women like Sarala Devi Chaudhurani, Kadambini Ganguly and Chandramukhi Bose, who did not pick up weapons, but urged literacy and education for girls and championed women’s rights and protections, paving the way for several reforms for girls and women in pre-Independence India — a war of a different kind.

In her memoir, Das recalls how the library at Bethune College in Calcutta shaped her life by allowing her access to books on the theories of revolution and freedom, and encouraged her ideas and hopes for a nation independent from British rule. In addition to churning out women who went on to become revolutionaries, the institution was remarkable for several other reasons, the foremost being that when it was turned into a college in 1879, it became the only institution for higher education for women in Asia.

Uttara Chakravorty, a former teacher of history at Bethune College, who spent approximately five years conducting research on the history of the institution, believes that the college library particularly played an important role in shaping the lives of the women who passed through its gates. “We didn’t find records of teachers imparting revolutionary views, but the library was good and the girls read newspapers,” she tells indianexpress.com . The college itself had no role to play in the formation of revolutionary views, but it was the diverse peer group to which women had access in the institution that fostered an exchange of ideas, believes Chakravorty. “The peer group consisted of girls who came from undivided Bengal. There were Jewish girls, Afghan girls, Anglo-Indians. The cosmopolitan nature of the environment shaped their views, along with the (college’s) architecture. The library had books of all kinds.”

When Kadambini Ganguly and Chandramukhi Basu graduated from Bethune College in 1881, they became the first two women graduates in the subcontinent. “This was the most revolutionary thing at that time,” says Chakravorty. Ganguly’s achievements were particularly extraordinary for a woman back then. Not only was she one of the first two women graduates, but she was also the first South Asian woman physician, with training in western medicine.

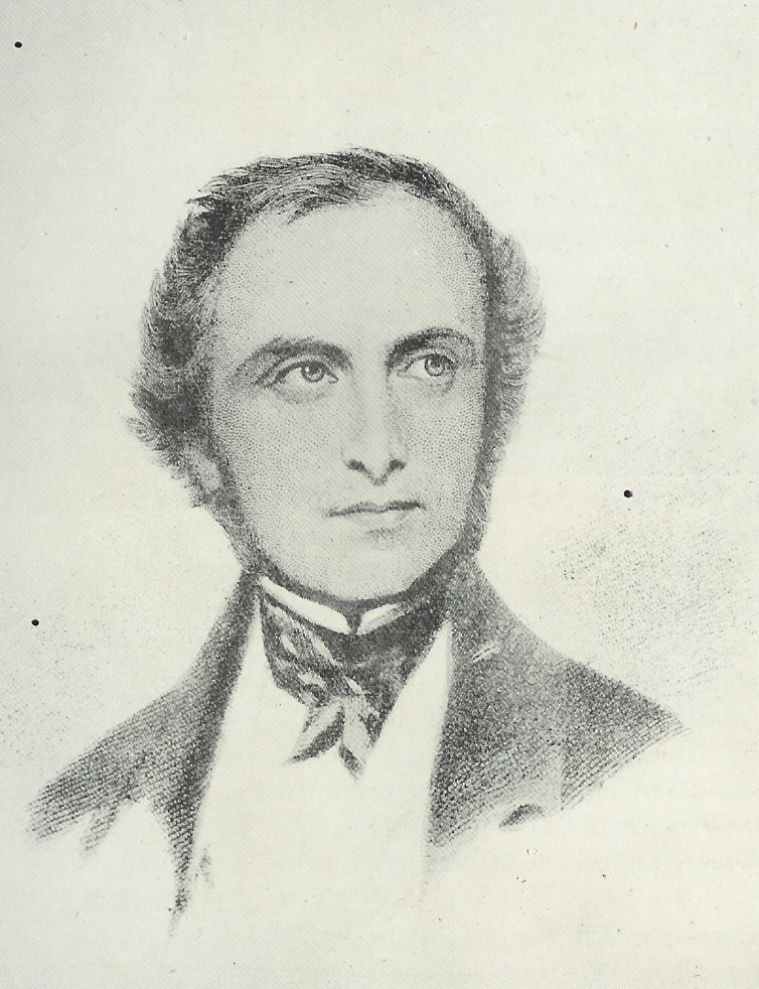

After John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune arrived in India in 1848, as a Legal Member of the Governor-General’s Council, he was appointed president of the Council of Education. Bethune’s posting allowed him to meet members of the Bhramo Samaj, who like him were also proponents of education for girls and women. In one of his meetings in the city, zamindar Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee gifted Bethune five and a half bighas of land for building a school that opened as ‘Calcutta Female School’ in May 1849 with 21 girls on the roll, an institution that became the predecessor of the Bethune School.

According to Kalidas Naga’s writings in ‘Bethune School And College Centenary Volume 1849’ published in 1949, “none but the girls of respectable Hindus would be admitted”. A school carriage was arranged to transport the girls who lived at a distance to and fro from school.

It was the first public institution for girls’ education, and was government-run. Although the school’s administration experienced some success in finding families interested in educating their daughters, the conservatives in Indian society rose up in protest against the school, discouraging their neighbours and relatives from sending their girls to study there. Families who succumbed to the social pressure withdrew their girls, till the number of students dwindled to just seven. The scenario changed by the end of the year, writes Naga, because some girls came back, increasing the number of students on the roll to 34.

Bethune’s initiative appears to have inspired philanthropic Indians to engage in similar endeavours. For instance, Raja Radhakanta Deb soon started a school for girls inside his large rajbari in Sovabazar, 15 days after Bethune’s institute started operations. After opening the Calcutta Female School, Bethune then purchased a new plot of land belonging to the Government of Bengal in Cornwallis Square, adjacent to the Calcutta Female School, and established another educational institution for girls, called the ‘Hindu Female School’ in 1849 with significant financial support from Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee.

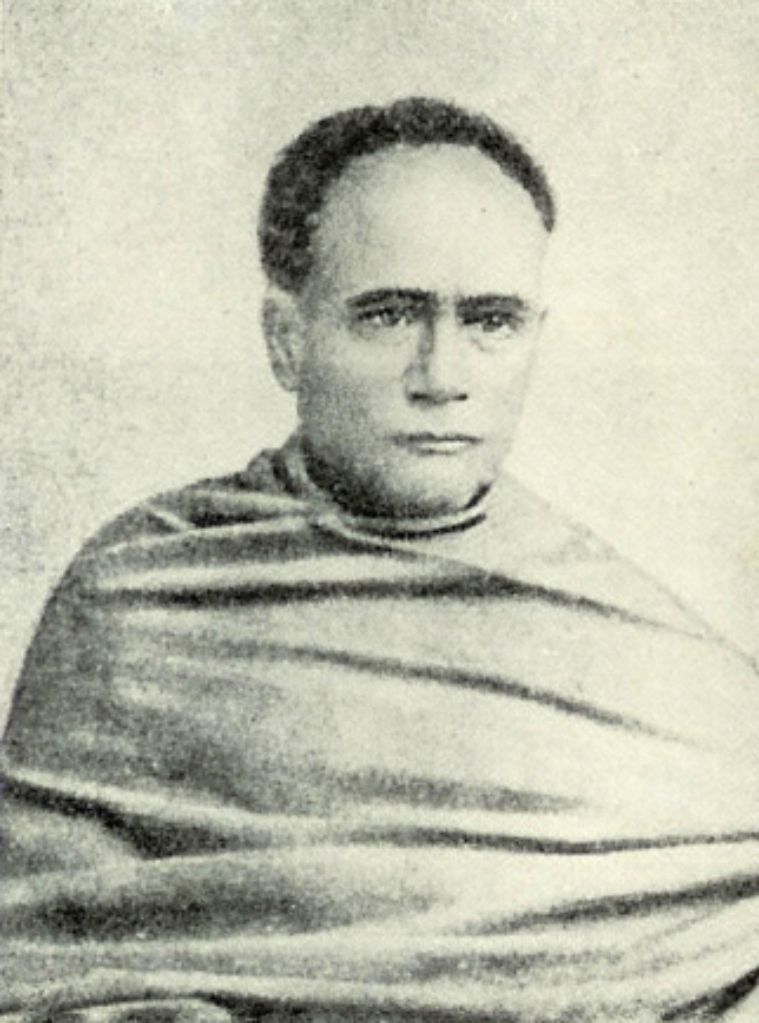

In December 1850, Bethune appointed Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar as secretary to the school, in what proved to be a masterstroke. Naga writes that Vidyasagar’s biographer Sambhu Chandra Vidyaratna acknowledged in the biography that this appointment encouraged many Hindu families to send their girls to Bethune’s school.

Thirty years after its founding, the school became a college, named after its founder. Chakravorty believes that the architecture of the building deeply impacted the students who enrolled in the institution, more than one realises. “It is a one-storey building with an open courtyard. There are Corinthian columns with a supporting pediment and a sculptured balustrade,” she explains. Built in the neoclassical style, the design included an open terrace and wooden french windows, a lot of which can still be seen on the building’s exterior.

“The openness of the layout was attractive to the girls, who were till then confined in their homes. Many of the girls wrote about (the architecture) in their memoirs. It did have an impact on their lives,” says Chakravorty. Chameli Basu, a gifted student who later went on to teach Physics at her alma mater, and passed out in the same year as Bina Das, specifically mentions the architecture of the institution. “She came from a conservative family and the openness of the space was overwhelming for her.”

While many teachers of Bethune College were Indian, the heads of the institution for the longest time remained English. In texts that Chakravorty found in the college library during her research, records of one particular incident stands out, she says. “The first mention of the student’s political consciousness can be found in a text in the college library from 1915. Anne Louis Janeau, the principal of Bethune, wrote that the students once wanted to go to a religious meeting but she suspected it was a political gathering.” It is one of the earliest records that indicate that although the institution was established for the education of Indian girls, there was little tolerance for ideas and initiatives that could be perceived to be anti-British in nature.

One of the most significant incidents in the history of Bethune College occurred when the Simon Commission arrived in 1928. This incident finds mention in Bina Das’ memoir where she recalls how she along with a group of fellow students, organised their first student protest against the Commission and faced threats from the college administration and Mrs. Wright, the English principal, if they did not apologise. Wright and the Director of Public Information collectively warned the students that if they didn’t return to their classes, they would be expelled and their scholarships would be withdrawn.

Led by Das, the students refused to comply and the agitation became so strong that it spread outside the college. Das recalls in her memoir that Wright, “the overbearing Englishwoman”, was forced to resign from service and was compelled to leave the institution. This protest was one of the most important occurrences in the history of the institution and the college has an entire file on the subject in its archives today. “It wasn’t just a struggle, but an active choice to get involved,” says Chakravorty of this protest.

The 1930s were turbulent times with more students becoming actively involved in the freedom struggle. “The girls were inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution. Kamala Das Gupta wrote in her memoir that most of the girls read banned books that were hidden under their textbooks; books like Pather Dabi, Maxim Gorky’s Mother,” says Chakravorty.

Chakravorty recalls the writings of Malati Guha Ray, an exceptional student at Bethune, who wrote in her memoirs of an incident when British police descended upon Bethune College in search of Kalpana Dutta, a member of the underground group Chhtari Sangha, who had left the institution to engage more fully in revolutionary activities. “Guha Ray wrote about how the principal was unhappy that students were participating in revolutionary activities and banned groups.”

By the 20th century, other educational institutions for women started opening up in Calcutta, like Loreto College, a morning section at Ashutosh College only for women and Victoria College. “When Presidency (College, now named University), started taking in women in 1944, Bethune began losing out on bright students who were more attracted to Presidency,” says Chakravorty.

The former students of Bethune haven’t mentioned teachers as inspiration in their struggle for India’s freedom, says Chakravorty, but the role of the institution cannot be discounted for the opportunities that it provided to women at a time when they were so few in number. Over 171 years after it first began as the ‘Calcutta Female School’, the only pathway for formal education for women in Asia, Bethune College’s own role as a revolutionary institution can perhaps only be fully understood in a re-reading of the memoirs of the lives of the women it shaped and altered over the decades.

source: http://www.indianexpress.com / Indian Express / Home> Research / by Neha Banka / Kolkata – August 14th, 2020