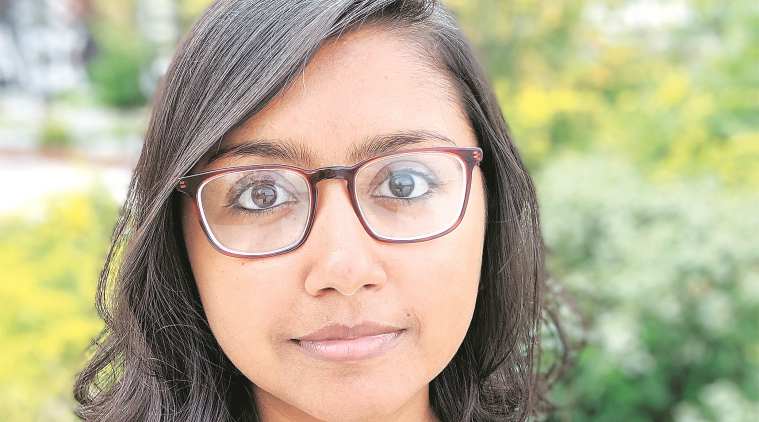

How New Yorker Megha Majumdar went from being ‘not good in English’ Kolkata girl to talk-of-the-town debut novelist.

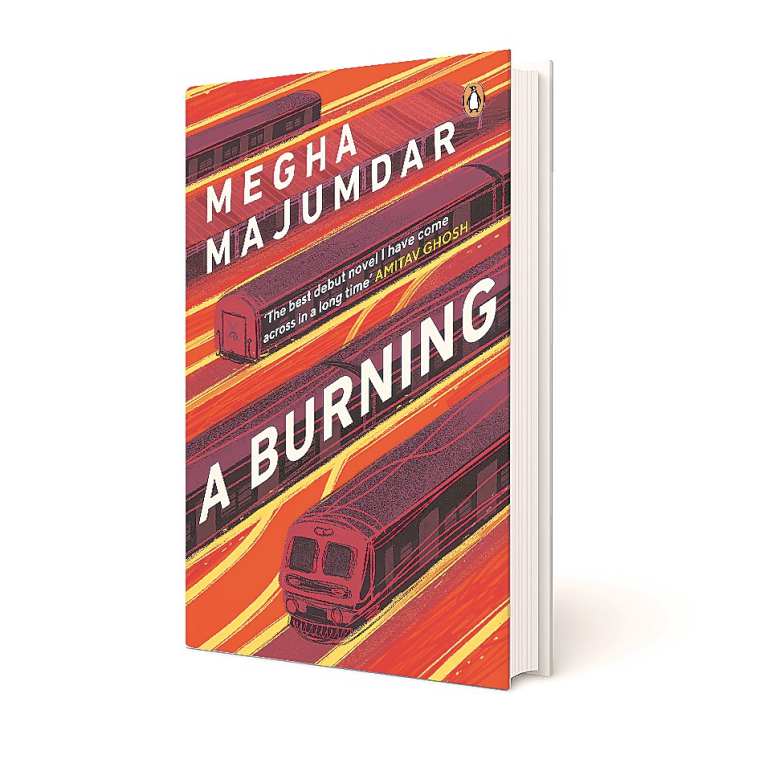

Days before Safoora Zargar, the Jamia Millia Islamia student in jail for protesting against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act , is denied bail for a third time, and while protests against the murder of George Floyd, an African-American man, are spreading across the USA, I am on a video call with Megha Majumdar. The buzz around the 32-year-old New Yorker’s debut novel, A Burning (Rs 599, Penguin Hamish Hamilton), that releases tomorrow, has been dizzying long before its publication. Generous blurbs by Amitav Ghosh and Yaa Gyasi have lauded the book as a zeitgeist of our times; James Wood of The New Yorker remarked on its “extraordinary directness and openness to life” that lays out a patchwork of inequalities in which we might recognise the patterns of our communal lives.

Yet, there’s a strangeness to this time in which fiction’s grip over reality has begun to appear jaded. As an incessant stream of horrors in our sociopolitical lives inures some to its potency and wears others out with outrage, nothing, it seems, can be more aberrant than the present. “This is a difficult, fatiguing time across the world,” acknowledges Majumdar, “So much of this moment here in the US is about historical reckoning. And, of course, I have been following the trajectory of the right wing in India. Scholars and journalists have made the connection between Hindu nationalism and white supremacy. In my book, I wanted to write about people. I wanted to write about how people dream and strive and laugh under oppressive systems.”

A Burning is a quiet, searing study of the underclass and the aspiring middle class in India, whose tentative stake in the capitalist economy is complicated by the many tyrannies of gender, religion and class endemic to society. When Jivan, a Muslim girl from a Kolkata slum, one of Majumdar’s three protagonists, reacts to hate posts against her community on Facebook after a suspected terror attack, with anger and sorrow, but also with a bit of bravura, one knows there will be consequences. “If the police didn’t help ordinary people like you and me, if the police watched them die, doesn’t that mean that the government is also a terrorist?” she writes on Facebook. Retribution is swift — the police come for her soon after. Her social-media friendship with a stranger linked to the case is documented as her complicity and her presence at the railway station on the fateful evening that a train is torched, leaving nearly a 100 dead, as evidence. In one swift action, Majumdar takes readers to the heart of New India, where personal and political ambitions are served or upended by a growing Hindu nationalist churn.

Majumdar’s assured narrative is propelled forward by two other characters linked to Jivan — PT Sir, the physical-education instructor in the school where she was an EWS student, who is drawn to the local right-wing political party, and, Lovely, a transgender woman, whom Jivan taught English, and who dreams of becoming an actor. “I wanted to explore specific questions with each of my characters. Jivan works hard to achieve her goals, which are pretty straightforward — she wants to rise to the middle class. She wants to own a smartphone and work at a mall. Unfortunately for her, she is caught in an oppressive system in which you can do everything right and still be thwarted. With PT Sir, I wanted to examine what a small taste of power could do for a middle-class man like him. What would he surrender, whom would he betray?” says Majumdar, who works as an editor in an indie publishing house, Catapult.

Majumdar grew up in the communist party-governed Kolkata in the Nineties, when the country was waking up to the charms of liberalisation. Change was also afoot in India’s political narrative. In December 1992, kar sevaks aligned to the VHP and BJP would demolish the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, that would set off a chain of reactions across the country. Majumdar doesn’t elaborate on when she became politically conscious. “We watched the news that our parents did. We were aware of what was happening around us,” she says. She would leave the city for the US in 2006 to study social anthropology at Harvard University and to graduate school at Johns Hopkins afterwards. But she would carry with her the minutiae of life on the city’s streets.

A Burning pulsates with the cadences of everyday life, the ebb and flow of ambitions, aspirations, disparities and disappointments. As an editor, Majumdar has been familiar with the publishing process, but the book’s reception in the US — touted as one of the best literary debuts of the year — did catch her by surprise. “I’ve been grateful for the positive early attention,” says Majumdar, who has begun work on her second book.

Her editorial expertise shows up in the craft of the novel, in the teasers she throws in by way of episodic interludes, in the cinematic pace with which she alternates between the narrative voices. A Burning is a novel firmly of the here and now, but Majumdar packs in layers of history in her idiosyncratic use of the English language. In West Bengal, the Left-front government had abolished the teaching of English at the primary level in government and government-aided schools in the state since 1981.

It would be brought back to primary classes nearly two decades later, but entire generations grew up with a shaky hold over the language. Overnight, Kolkata would see a proliferation of tuition classes offering lessons in English. Majumdar remembers attending one as a child. In the first year that her parents applied to put her in primary school, she didn’t make it anywhere — “My English wasn’t very good,” she says. So, she was enrolled for English tuitions. The next year, she joined a private school. It was the beginning of a deeper engagement with the language. “A lot of my childhood was spent in public libraries and in second-hand bookstalls, borrowing all kinds of books to read,” she says.

The subtlety with which Majumdar moulds language to the spirit of the city and its inmates rings out best in the voice of her most endearing character, Lovely, who speaks in broken pidgin English that fits into the nooks and crannies of her life. Lovely’s vitality relies on visceral experiences acquired during her travels through the city, and minute observations that make up for a lack of formal education. It is here, in the authenticity of the polyphonic voices that people her fictional landscape, that Majumdar’s novel soars.

Like Deepa Anappara’s Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line earlier this year, the exhilarating response to A Burning in the West owes a hat tip to ticking all the boxes that make the India story familiar — jagged inequality, religious roil and irrepressible hope. “I wanted the book to be legible and inviting for those who have never been to India and do not follow Indian news, as well as to those who have lived in India all their lives. I wanted the book to be an act of invitation, to open imaginative doors to the many different, complex stories that one might follow,” she says.

source: http://www.indianexpress.com / The Indian Express / Home> Books & Literature / by Paromita Chakrabarti / June 14th, 2020