‘Goopi Gyne Bagha Byne’ (1969) onwards, he was the still photographer for all of Satyajit Ray’s works till his last film ‘Agantuk’ (1991)

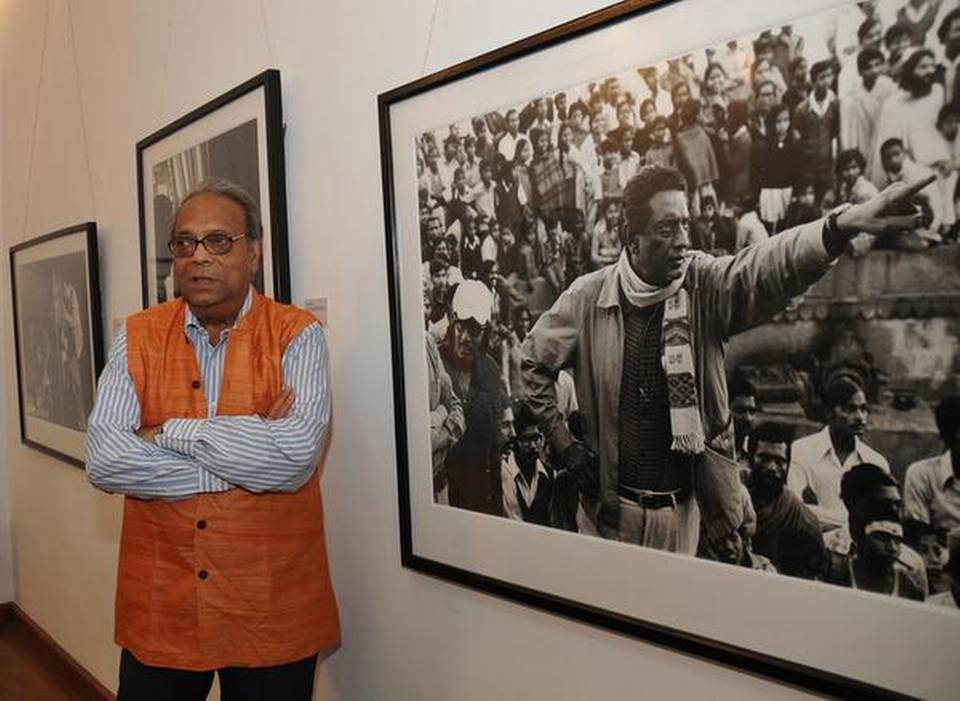

For someone best remembered as the visual biographer of legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray and a documentarian of the making of his astounding body of work, an interesting aspect about Nemai Ghosh was that he started off as an actor with actor-director Utpal Dutt’s Little Theatre Group in Kolkata.

Arts critic and publisher-editor Samik Bandopadhyay remembers one such play that he acted in: the landmark Angar (1959) about the exploitation of coal miners. It had music by Ravi Shankar and complex sets (Nirmal Guha Ray) and lighting design (Tapas Sen) with an entire sequence of a mine getting submerged under water. “He was an impressive and formidable figure on stage but was never so interested in photography then,” recalls Mr. Bandopadhyay.

Nemai Ghosh passed away in Kolkata on Wednesday. He was 85.

Ghosh’s interest in photography was kindled entirely by chance in 1966 when he found an abandoned camera and started tinkering and playing around with it. Being a great lover of cinema himself, he wanted to shoot the process of filmmaking which is when his path crossed with that of Ray. Initially just “tolerant” of his presence, as he once recalled, Ray discovered Ghosh’s talent by and by to have him become a part of his unit. Goopi Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) onwards, he was the still photographer for all of Ray’s works till his last film Agantuk (1991). “The only other parallel I can draw is Raghu Rai’s photographs of Indira Gandhi,” says photographer Chirodeep Chaudhuri of an imagemaker’s consistent collaboration and engagement with a personality.

Ray’s son and filmmaker Sandip Ray remembers meeting him on the sets of Goopi… “He was a part of the family. He was always there, not just on the shoot, but our home as well,” he says.

Black and white

The magic of his black and white images lay in the specific fleeting instants that they managed to capture, that too without flash, in natural light. “He never missed a moment, captured the right moment,” says Sandip Ray. “His work in theatre gave him a sense of the moment,” says Mr. Bandopadhyay.

Filmmaker Sujoy Ghosh compares his frames to videography. “Each of his photos tells a story to me. Like Jaya Bachchan in Kalighat, teeka on the forehead, prasad in hand, happy… I see many things in the process. It’s instructive and informative about the process of filmmaking itself,” he says.

Mr. Chaudhuri points out the candidness in his frames unlike the “manufactured PR images and ‘behind the scenes’, ‘making of’ balderdash” where the stars are perennially performing or posing.

“There was an endearing quality about his photos. You could see his love for theatre and cinema [reflected in them],” says Mr. Chaudhuri.

Apart from Ray, Ghosh also chronicled some of Mrinal Sen’s films and he was the still photographer on Mira Nair’s The Namesake. “His portraits of my father were absolutely brilliant,” says Mr. Ray. Sujoy Ghosh remembers him shooting on the sets of his own film Kahaani. “I fell at his feet. It was such an honour that he considered our film,” he says.

On theatre

Beyond Ray and films, a major part of his work was on the theatre in Bengal and about Kolkata itself. His work was a reference point for Sujoy Ghosh when he went shooting in Kolkata for Kahaani. “It was an amazing inspiration. Every photographer and painter has a [unique] way of looking at places, objects, people which is different from ours,” he says.

Mr. Chaudhuri remembers him showing rare colour photos of Ray when he visited Ghosh at his home couple of years back. “He was so excited going through the folders and files of his work on the computer,” he says. One of Ghosh’s disappointments, according to Mr. Chaudhuri, was not being given space by the State government to archive his work. Later, he gave away most of it to the Delhi Art Gallery.

In the latter half, he was passionately documenting painters at work and musicians in performance. According to Mr. Bandopadhyay, Ghosh had clicked some exclusive pictures of the ailing Italian maestro Michelangelo Antonioni, some of them in his hotel room, when the latter had come to Kolkata for the retrospective of his work at the International Film Festival of India in 1994. Impressed with his images, Mr Antonioni, who had taken to painting in his later years, had invited him for his exhibition to Italy. Ghosh took pictures of Antonioni moving around in the exhibition on a wheelchair. Having been witness to and documented the maestro’s painting phase, Ghosh wanted to preserve them in the form of a book. Sadly there were no takers for it in the commercial publishing world.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Entertainment / by Namrata Joshi / Mumbai – March 26th, 2020