To the northwest of Tokyo’s imperial palace, the Yasukuni Shrine is a 148-year old complex of memorials and cherry tree-dotted grounds, commemorating those who died in the service of Japan between 1869 and 1947.

It has emerged as the symbol of Japan’s fraught relations with its neighbouring countries and its own uncomfortable relationship with its Second World War history. Among the two million people buried there are 1,068 convicted war criminals. Fourteen of these are categorised as ‘Class A’ criminals, found guilty of a special category of “crimes against peace and humanity” by the 11-member team of justices from Allied countries that made up the 1946 Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

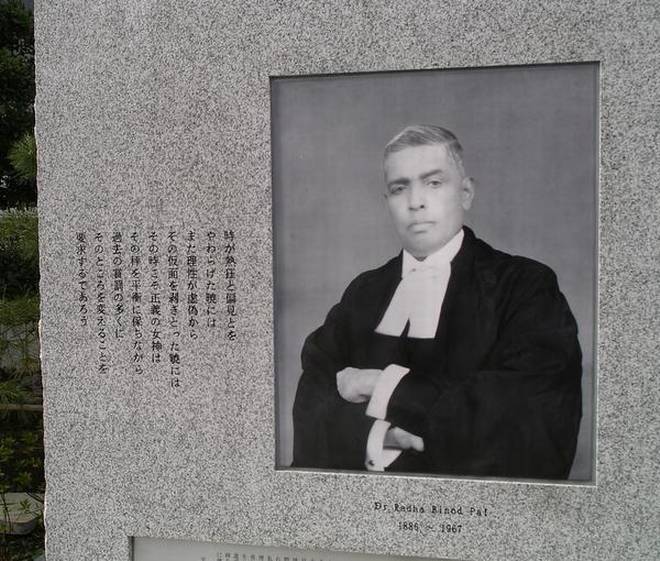

Visits to Yasukuni by senior Japanese politicians are viewed by neighbouring countries, in particular China and South Korea, as provocations, tantamount to a denial of war crimes. Japanese nationalists believe Yasukuni visits to be a justified exercise of sovereignty, indicating a moving on from what they consider to be an overly apologetic stance to the war. On the day this correspondent visited, there were scant traces of these bitter recriminations. A series of memorials dedicated to military horses, pigeon carriers and dogs charmed camera-wielding tourists. But the plaque attracting the tightest knots of visitors featured a large black and white photograph of an Indian judge: Radha Binod Pal.

In Japan, this Bengali jurist elicits the kind of recognition and reverence that other countries reserve for the likes of Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore. Biographical mini series about the judge are aired on Japanese TV, memorials to him have been erected in Tokyo and Kyoto, and books debating his legacy are published every few years. The average Indian would be hard-pressed to identify Justice Pal at all. Until the war, he was best known for his contributions to the Indian Income Tax Act, 1922. His international profile comes from his participation in, and eventual dissent from, the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

Twenty-five of Japan’s top wartime leaders were convicted by the tribunal of the new category of ‘Class A’ charges. Going against the grain of Allied judgment, Pal issued a 1,235-page dissent in which he rejected the creation of the ‘Class A’ category as ex post facto law. He further slammed the trials as the “sham employment of legal process for the satisfaction of a thirst for revenge”. And he argued that the nuclear incineration of Hiroshima and Nagasaki should also be counted as major war crimes.

Procedural flaws

The Indian judge tends to be valorised by Japanese nationalists and historical revisionists who seek to deny Japan’s wartime culpability. But in fact the jurist did not absolve Japan. His intention was rather to highlight the flaws in the legal process of the trial. Since all the judges were appointed by victor nations, the Indian justice thought the trial to be biased and motivated by revenge.

In his 2007 book on Pal, Takashi Nakajima, an Associate Professor at Hokkaido University’s Public Policy School, criticises right-wing supporters of Pal for relying on out-of-context quotes from the dissenting judgment. Pal’s dissent ran to a quarter of a million words, but Prof. Nakajima says that only a handful of quotes tend to be used by historical revisionists as ballast for their agenda.

Back at the shrine, a Japanese tourist gazed at the Pal memorial, silently mouthing the words written on the plaque: “When Time shall have softened passion and prejudice… then Justice, holding evenly her scales, will require much of past censure and praise to change places.”

(Pallavi Aiyar is an author and journalist based in Tokyo)

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> News> Tokyo Despatch – International / Pallavi Aiyar / November 18th, 2017