Monthly Archives: July 2020

30

29

28

27

26

25

24

Why the Internment of Chinese Indians Is a Story That Must Be Told

When citizens become enemies, such an episode cannot be cannot be pushed to the recesses of public memory.

It’s in the nature of history that some stories are seldom told, if at all. The story of the Chinese community in this country, summarily packed off to internment camps after India was defeated by China in the 1962 war, is one such episode pushed to the recesses of public memory. There has been little discourse around the subject, and no official acknowledgement of the injustice done to the Chinese Indian community.

Rita Chowdhury rescues that slice of history from oblivion in her historical novel, Chinatown Days. First published in Assamese in 2010 with the title Makam (named after the main Chinese settlement in the region), the book brings those fraught years to light. Overnight, Chinese Indian families were yanked out of their homes, split up, and herded onto trains to spend an unknown number of days, months, or even years in a prison camp in Deoli, a town in Rajasthan. A bewildered and anguished community tried, in vain, to make sense of its sudden degraded status as prisoners.

Chinatown Days reveals how wars scapegoat people who have nothing to do with lighting or stoking the fire. People who simply happen to be on the wrong side of history at a juncture – like that one – when passions are riled up, and governments are locked in war. The stigma of internment, along with the absence of social and political conversation around the injustice, drove survivors of the Deoli camps into silence for nearly five decades.

As a fresh conflict between India and China surfaces with scenes of politicians and ordinary citizens calling for boycotting Chinese goods and trades , we may recall the plight of the Chinese community that suddenly found itself hemmed in from all sides because of a war that was not of their making.

Earlier this year, in their book, The Deoliwallahs: The True Story of the 1962 Chinese-Indian Internment, authors Joy Ma and Dilip D’Souza used interviews to capture the voices of the Chinese community, spanning generations, now dispersed across India and the rest of the world.

Born in Deoli, in her section of the preface, Ma writes : “The Camp is something I lived with from the earliest moment … For us, the survivors of the interment … the stigma and effects have lasted a lifetime, made deeper by the lack of information about the incident. And the experience remains hard to forget no matter how far we have come.” She now lives in the US.

Survivors speak of their experiences in the documentary, Beyond Barbed Wires: A Distant Dawn, saying that even a word of apology from the Indian government would go some way in helping them negotiate the past and heal its wounds. “The total population of Kolkata’s Chinatown was around 30,000, After 1962, there are hardly 2000 Chinese living in India,” Ming-Tung Hsieh, a former detainee, says in the film.

If and when they see the light of day, such narratives show the fragility of existence in a country that you may not have been born in, but one you have embraced as your own, and have been living in for generations.

The genesis of the Chinese community in India dates back to at least the 19th century, when the British East India Company hired workers from China to launch the tea industry in India. Citing Kolkata’s National Library records, Jaideep Mazumdar, in an essay, identifies Yong Atchew as the first Chinese person to settle in Calcutta in 1780. Atchew launched a sugar mill around which grew one of India’s first Chinese communities. By the middle of the 19th century, there was a sizable Chinese population living in India. And at the time of Indian independence, descendants of the early Chinese workers – some of whom were transported to the country as slaves – had become integrated with local cultures, considering themselves citizens of India.

A group of Chinese workers brought to Assam by the East India Company in the 1830s, many of them indentured or trafficked, form the Chinese community in Chowdhury’s novel. At a time when the ‘outsider’ vs ‘insider’ debate in our public and private conversations has become layered with such corrosiveness, Chowdhury portrays a seamless assimilation of the Chinese community within Assamese society. Assamese and Chinese women and men get married into each other’s communities, the Chinese speak fluent Assamese, while the Assamese eagerly wait for the celebrations of the Chinese New Year. Chowdhury’s novel closely follows the reality of the times. In today’s acidic atmosphere of suspicion, one wonders if this is what utopia looks like.

The India-China war, and particularly India’s humiliating defeat at the hands of the Chinese, in one swoop destroyed that equilibrium. The Indian government, then headed by Jawaharlal Nehru, chose to treat the Chinese community as ‘enemies’ for their association with the enemy country, even though China was not just geographically but culturally distant to the Chinese community in India. Overnight, Chinese Indians across India, particularly in the Northeastern regions and Kolkata, became suspects in the eyes of the government and society. Chowdhury presents a vivid portrayal of the police suddenly appearing on the doorsteps of unsuspecting people, giving them barely ten minutes to leave for an unknown destination, ordering them to leave behind their belongings.

The parallel with Japanese Americans

The story of the wartime incarcerated Chinese prisoners finds a parallel with the internment of over 1000,000 Japanese Americans after the attack on Pearl Harbour during the Second World War in 1942. In reaction, then US president, Franklin Roosevelt, signed an executive order forcing Americans of Japanese ancestry to be removed to concentration camps for five years. Almost two-thirds of the detainees were Japanese Americans, born in the US. They had never visited Japan. In 1988, Ronald Reagan signed the ‘Civil Liberties Act of 1988,’ formally apologising for the internment of American citizens. This happened, in no small measure, because ordinary Americans protested and spoke out against the incarceration of fellow citizens.

“The Chinese Indians did not have any civil liberties group supporting them. Not one group – not one person objected to internment of Chinese Indians. Deoli camp was done like a playbook from Japanese internment … but for the lack of representation in India … there is very little support from groups…” said Joy Ma in a conversation around the book.

The former Chinese detainees still await an acknowledgement of the injustice done to their community. There are still questions hanging in the air: Who accepts you as a citizen? Who will stand by you in a time of crisis? What happens to a community if the country they believe to be their own enters into war with the country of their ancestors?

I scarcely need to point out that these questions have not gone away, for those who suffered that injustice, or those who suffer injustices that are still ongoing.

source: http://www.thewire.in / The Wire / Home> Analysis> Rights / by Monobina Gupta / June 23rd, 2020

Remembering Uma Bose, who presaged a new era for vocal music

‘The Nightingale of Bengal’ died of tuberculosis on her 21st birthday.

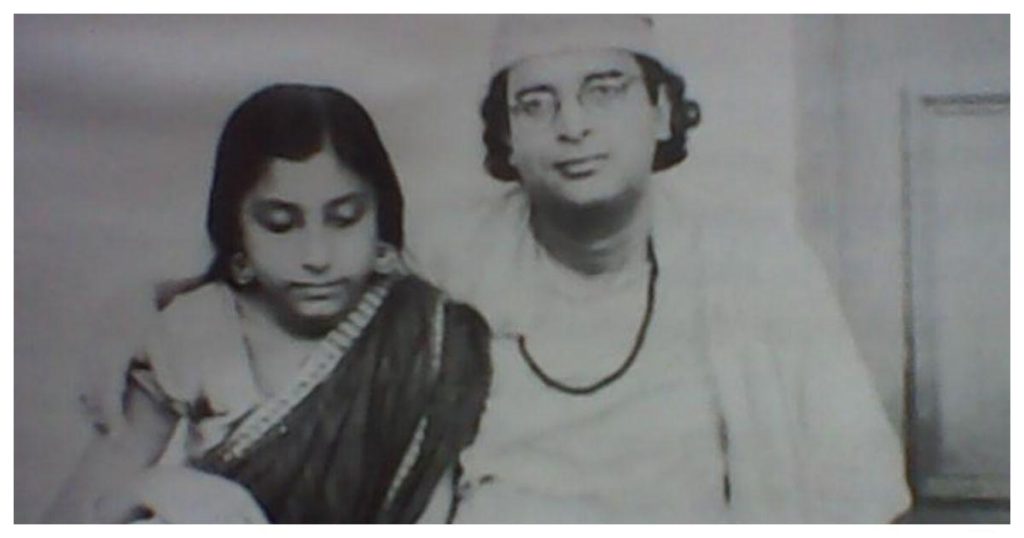

I heard about Uma Bose from my mother when I was a child. She spoke of her with unusual regard, and with sadness and wonder. Uma Bose was born to an eminent, well-to-do family in Calcutta on January 21, 1921, and she died on her 21st birthday of tuberculosis, in 1942. I was told her younger brother had already died of TB and that this had broken her heart.

The wonder and sadness in my mother’s references were mixed up with each other when she dwelled on the symmetry of the life and death, the cruelty that had cut off Uma Bose’s life as a singer and the abundance of fortune that had given her a singular timbre and astonishing mastery well before she died, when she was still half a child.

Uma Bose learned Hindustani classical music for a period from Vishmadev Chatterjee, but her métier became a new kind of modern song that was emerging in Bengal after Tagore, a rival to, and precursor of (in terms of musical and orchestral innovation), the revolution that would change film music in Bombay in the 1950s and ’60s.

To this kind of music she brought a classical proficiency, and a classicist sophistication and calm, whose character was absolutely modern, and I think unheard-of in the 1930s – prefiguring the contained virtuosity and the classicist poise that Lata Mangeshkar would bring to film-music singing in the 1950s.

Her reputation was built on being among the first interpreters of the songs of Himangshu Dutta, one of the great innovators of the popular song in the twentieth century (I’m not qualifying this with “in Bengal” or “in India” for good reason), and on her renditions of the songs in the demanding, eccentric repertoire created by the scholar-poet-singer-mystic Dilip Kumar Roy (1897-1980), son of the poet and songwriter Dwijendralal Ray (1863-1913).

The two songs I’ll first draw attention to here – their tunes are composed, and music arranged, by Himanshu Dutta – are Akasher Chaand (The moon in the sky) and Chaand Kahe Chameli Go (The Moon Says, O Chameli). The first is from 1940, when Uma Bose was 17 years old; the second from 1938, when she was just 17. These are part of a series of songs whose words Dutta got his lyricist friends to write, about the abortive love between the moon and the chameli flower.

Listen first to the curious but arresting mix of instruments – the electric slide guitar; a horn; the sitar; the mix of a three-note orchestral bass line and very light tabla in the 1940 song; the deliberate abstention from tabla in the 1938 arrangement, where rhythm is provided solely by bass lines on strings which don’t, however, interfere harmonically with the song’s ethos but add an unprecedented texture.

I can hear no Indian instrument in Chaand Kahe Chameli Go.

Notice the tunes themselves. Akaasher Chaand sounds like it’s based on a raga, but it’s a mix of three – Kamod, Kedar, and Gaud Malhar – that all approximate the major scale and all use both the ma and tivra ma; that is, the natural and sharp fourth. These two notes are revisited to extraordinary effect midway through the song by both Dutta’s composition and by Uma Bose. It’s the kind of subtle but revolutionary modulation on compositional thinking made possible by Tagore, which Dutta extends also to his arrangements.

There is nothing comparable to this testing of demarcations in the Western popular music of the time. In Aakasher Chaand, Bose uses her classical training to play with complex melodic phrases from 1.16 to 1.20 minutes, but brings to the song a deep tonal tranquility and fullness that she takes from her training in, and deep feeling for, the khayal: there is nothing “light” about her approach.

In Chaand Kahe Chameli Go, the melody, which has no counterpart in a raga (the closest is Chhaya Nat), is transformed into an Indian song by the singer and the composer through the use of meend, or North Indian classical music’s glides between notes. You wouldn’t notice that the tune isn’t an actual raga, given the interpretation – but if you sing the opening notes without the meends, you’ll see the melody is very like a Western marching tune or drinking song.

These compositions and renditions aren’t attempts to mix things up; they are a new way of thinking about music.

Uma Bose’s mentor was Dilip Kumar Roy, the son of a great poet and songwriter, a cosmopolitan who went to Cambridge to do his Tripos but turned more and more to music (he was a gifted and trained singer), experiments in musical composition, and mysticism. To understand figures like Roy – and others before him and contemporary to him – and their particular rebellion, you’d have to imagine what our present-day cultural landscape would be like if some our public intellectuals, social scientists, historians, and commentators began to compose songs, turned out to be deeply tuneful singers with classical training, artists attempting to create a secular vocabulary in poetry and music to express a kind of surrender.

One recalls Nietzsche’s loathing of Socrates for his habit of over-determined theorising, but his warming to the Athenian because the latter set aside philosophy as a condemned man and began to learn music shortly before his death. To understand the revolution that people like Roy (and before him his father Dwijendralal, and his father’s contemporary Tagore) undertook against the colonial self, which could be figured as a kind of Socrates, one must understand the release that the arts, especially modern music, constituted. This release made them extend themselves and their sphere in a way unknown to our intellectuals today. It’s in the midst of this revolution in the educated middle class that we should also place Uma Bose’s singing.

Here are two compositions of Dilip Kumar Roy’s, sung by Uma Bose, both combining devotional elements with Hindustani classical ones, their taans or complex melodic patterns containing echoes of operatic coloratura. They’re like idiosyncratic blueprints of projects that could only have been attempted by an inventor who had access to a multiplicity of cultural languages, techniques, and experiences. They are abstractions, really; it takes Uma Bose’s voice and abilities as an experimental singer, which is what she becomes in these songs, to breathe life into them.

This is Rupe Barne Chhande, loosely based on Khamaj, and Jibane Marane Esho, an invocation of a devotional mood in raga Asavari.

I’m adding a third song here Ke Tomare Jante Pare, Dilip Roy’s father Dwijendralal’s peculiar but compelling riff on the kirtan form.

Uma Bose was conferred with the well-intentioned sobriquet “Nightingale of Bengal” by Gandhi in 1937. She’s little listened to today, in Bengal or outside it. Partly this may have to do with the unclassifiable character of Dilip Kumar Roy’s songs, which are also too difficult to hum to yourself. But mainly it owes to the dominance of an anodyne and sentimental version of the Tagore song that ruled over Bengal from the 1960s, and to a form of tremulous singing that Bengalis began to hold close to their hearts. (If you compare the 1966 version of Chaand Kahe Ghameli Go by Hemanta Mukherjee to Uma Bose’s, you’ll have an idea of this pervasive tremulousness.)

Outside Bengal, our understanding of the history of the popular song in India has been both enriched and curtailed by Hindi film music. It provides a definition that’s full of excitement and variety; but it is, itself, by no means definitive. Uma Bose, like the experimenters whose work she was integral to, was a pioneer. Her emphasis on purity of tone, and a technical accomplishment that goes well beyond precociousness, presaged a new era for vocal music.

Amit Chaudhuri is a writer, a Hindustani classical vocalist, and a composer of crossover music. Listen to his music here.

source: http://www.scroll.in / Scroll.in / Home> Acts of Retrieval / by Amit Chaudhuri / June 23rd, 2020