Image: The Telegraph

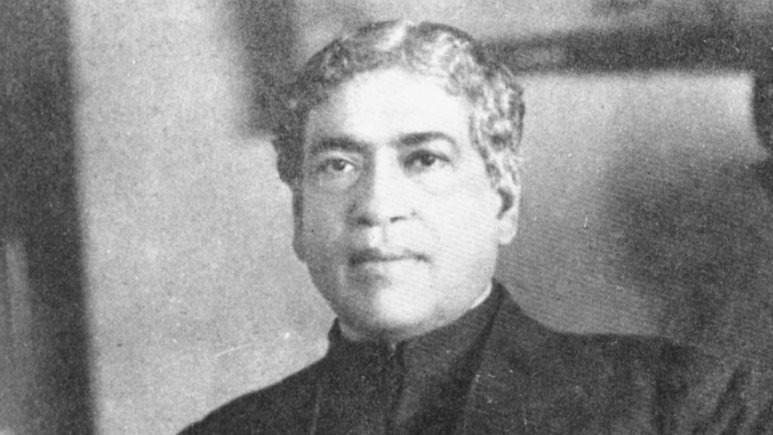

More than 100 years after Jagadish Chandra Bose conducted the experiment that established plants have life, a group of scientists in Calcutta came together this year to repeat it.

Supriyo Kumar Das, an assistant professor of Geology at Presidency University, led the initiative. The others on the team were also from Presidency — Debashis Datta and Rabindranath Gayen, both assistant professors of Physics, Snigddha Pal Chowdhury, a research associate in the Geology department, Abhijit Dey, an assistant professor of Botany, and Saranya Naskar, an MSc student of Physics.

Bose, who had joined Presidency College in 1885 as a professor in the Physics department, had conducted the experiment in a laboratory on these very precincts. No matter how much he is hailed today for his scientific genius, in his time Bose’s experiment had not been received well.

It all began when Peter V. Minorsky, a botanist and professor at Mercy College in the US, got in touch with Das earlier this year. Minorsky wanted to know about the groundwater composition in the College Street area, where Presidency University stands.

Says Das, “It is from him that I heard about the prejudices against Bose. In the course of our exchanges, I got interested and emotionally involved with Bose’s work.”

He had been savagely criticised by George James Peirce, professor of Plant Physiology at Stanford University. Peirce wrote in the journal, Science, in 1927: “The trouble with Bose… is that while his curiosity is directed to biological phenomena, his mind is inadequately equipped with the information and habits necessary for accurate study, and his reflections are addressed to philosophical problems.”

In 1929, the Indian Review reported that G.A. Perrson, who was from the US, was unable to find pulse in plants. And years later, in the mid-1960s, in the Handbuch der Pflanzenphysiologie (Encyclopaedia of Plant Physiology), it was said, “Unfortunately Bose’s theoretical views and his emotional style of reporting have generated what may be an excessive skepticism concerning the validity of his observations.”

This is what Bose had observed. By devising a wire electrode — an invention three decades ahead of its time — he identified a pulsating layer of cells abutting the vascular tissue in plants. In an email to The Telegraph, Minorsky says, “In the last few years, plant biologists have come to recognise this layer is the site of propagating waves of calcium release that are involved in communicating stress from local points of occurrence to the rest of the plant. The discovery of this calcium wave is one of the more exciting discoveries of the 21st century, and Bose’s ‘plant heart’ predates this discovery by a century.”

Bose has left notes aplenty about every aspect of his historic experiment. One of the lone omissions is the kind of water used. Says Das, “Being a geochemist and scientist, I understand the composition of groundwater and the effect of chemical stress of sodium on plants. I also know that the composition of water varies from place to place.” He adds, “It occurred to us that Bose’s peers in the West might not have got the same results as him because of the water used.”

Image: The Telegraph

In Bose’s time, water was supplied to the Presidency campus from Palta in the Barrackpore area. Das points to a spot occupied by an elevator on the ground floor of Baker Building that houses the Physics department and says, “This is where the old pipeline ran.” Currently, the municipality takes care of the water supply. It comes from the Tala tank in north Calcutta.

When Das and and others repeated the experiment, they decided to use water from every possible source Bose might have accessed. “He could have also used water from the Ganges or from the pond in College Square,” says Das.

Datta explains, “We wanted to check the potassium and sodium concentration. Electricity flows through water only when there are some ions present in it. Possibly, the scientists from the West had not used ionised water.”

The “repeaters” used for the experiment the plant Bose had used — the Desmodium motorium, locally known as bon charal. Minorsky explains, “The lateral leaflets of Desmodium are unique in the plant kingdom for their pronounced and unprovoked oscillatory movements. If conditions are optimal, one can watch these lateral leaflets move at a pace slightly slower than the second hand of a watch.”

According to Minorsky, Bose enjoyed certain enormous advantages over his Western peers. First, Desmodium motorium is a native of Bengal, so he had access to an ample supply of healthy, thriving specimens. In contrast, in the West its cultivation was restricted to glasshouses. Those days, glasshouses were often heated by wheelbarrows of burning coal. These released a gas called ethylene, which in turn affected many plant processes, including a decrease in overall excitability. Second, he points out Calcutta’s temperatures and how they lend themselves to plant study. “Temperatures of 30-35° Celsius, which occur commonly, are optimal for studying plant movements and excitability. The temperatures at which scientists in the West studied plants would have been much lower,” he says. Finally, there was the salty water advantage.

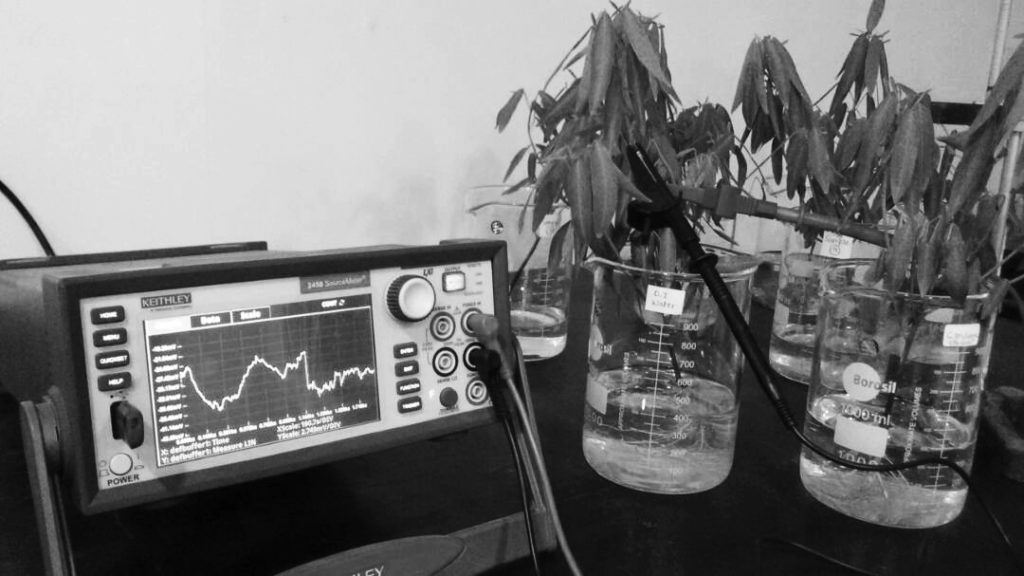

Dey arranged for 21 Desmodium plants. Each was kept in a beaker full of a distinct water sample. Thereafter, they were all kept in a controlled atmosphere. Says Gayen, “We placed them in glass beakers and left them in the laboratory, where all the lights would be kept on so that all of them were exposed to the same amount of light. The air conditioner would be set at a particular temperature to control the humidity. We would connect the probes to two different parts of the stem. The source meter was used to read the fluctuating signals.”

The brainstorming went on for months and the experiment lasted a fortnight. Das says, “The apprehension of failure was there. But the moment when we got the first response was exquisite. The horizontal line that appeared on the screen formed a peak and then fell only to rise again. Though our graph did not have peaks and troughs as tall as Bose’s, we definitely had got a graph that roughly replicated the ECG graph of humans.”

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph,Online edition / Home> Culture / by Moumita Chaudhuri / November 25th, 2018